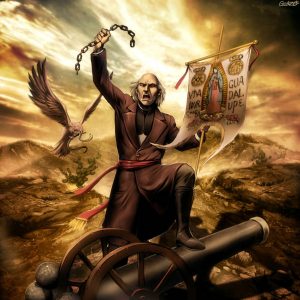

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla – Grito de Dolores

Art by GENZOMAN: https://genzoman.deviantart.com

For over 300 years between 1519 and 1821, the entire country we now know as Mexico was enslaved under the colonial power of Spain. Our people, the natural resources, the land and our government were all controlled directly under the kings of Spain, who sent their agents with instructions to attack, kill, and steal throughout Nuestra América, and carry out whatever orders the Spanish kings demanded. During that period in history the Spaniards had all the power over our gente, and they did whatever they wanted with us. They pillaged and murdered, and treated the great majority of indigenous people like slaves on our own land. For hundreds of years, they stole everything they could to take it back with them to Europe, especially native silver, gold, and other natural resources.

For over 300 years between 1519 and 1821, the entire country we now know as Mexico was enslaved under the colonial power of Spain. Our people, the natural resources, the land and our government were all controlled directly under the kings of Spain, who sent their agents with instructions to attack, kill, and steal throughout Nuestra América, and carry out whatever orders the Spanish kings demanded. During that period in history the Spaniards had all the power over our gente, and they did whatever they wanted with us. They pillaged and murdered, and treated the great majority of indigenous people like slaves on our own land. For hundreds of years, they stole everything they could to take it back with them to Europe, especially native silver, gold, and other natural resources.

To this day, people still argue that we will never know just how much silver the Spaniards stole from Nuestra América. Oral history tells us that a bridge made of pure silver could have been built over the Atlantic Ocean, so a person could walk from Mexico to Spain, and not get their feet wet. Some say that another bridge could be built, from Spain back to Mexico, but that one constructed entirely from the bones of the Indigenous and African people who died working in the silver mines.

Hoping to erase their genocidal thievery from our historical memory, Spaniards spent at least 300 years trying to destroy our indigenous culture, intent on making us forget the greatness of our native heritage. They burned our native books, destroyed our pyramids and spiritual artifacts, and they forcefully convinced many of our ancestors to think that Spaniards were superior to Mexicans and other indigenous peoples. The consequences of this colonial violence survives today, so much so that we all know someone in our own families who denies their indigenous heritage to instead pretend that they are from Spain.

Spanish colonizers stole not just silver and gold, but also every type of natural wealth we had in Mexico, including jewels, sugar, timber, tobacco, different foods and spices, animal skins, birds, etc. They took all of this loot back to Spain, and by doing so, they made Spain the richest and most powerful country in the world for over 100 years.

In fact, the birth of modern European capitalism was financed with the massive theft of native wealth and centuries of enslavement of African people. This was a moment known as the “primitive accumulation” stage of global capitalism. Meanwhile, for hundreds of years our people lived in extreme poverty, enslaved and exploited at the hands of the Spanish Europeans. Native pyramids were destroyed, and on top of the ruins of these indigenous temples, Spanish colonial governments set up their own buildings and Catholic cathedrals, often using the same stones pulled off of the original pyramids. Structures and artifacts of the Nahuatl, Maya, Mixtec, Zapotec, and other great civilizations of Mexico were blown apart or burnt to ashes.

Though they tried everything they could to wipe out our indigenous heritage, the roots of the native peoples survived in the rebellious Mexican spirit. The Spanish colonizers, like all colonizers who came after them, refused to understand that you can’t build a stable future when that future depends on the oppression of a native people. When oppression exists, resistance will, sooner or later, always be a decisive factor.

Late into the night of September 15, 1810, in the small pueblo now called Dolores in the State of Guanajuato, an important event took place that was led by a priest named Miguel Hidalgo de Costilla. That night, and into the early morning of the 16th of September, Miguel Hidalgo rang the bells of his church to wake up the people of the pueblo and the surrounding areas. When people gathered to find out what was going on, Hidalgo made a revolutionary declaration for the people to fight for freedom – “El Grito de Dolores” – and his call was heard throughout the country. He yelled out for everyone to hear: “Today we reclaim our lives and our future. Today we reclaim a revolution! ¡Viva Mexico!”

The next day, the 16th of September, Hidalgo announced major social and economic reforms, and declared an end to slavery throughout Mexico. To enforce these radical changes, Hidalgo and his followers began a revolutionary march throughout the State of Guanajuato until reaching the capital, Guanajuato City.

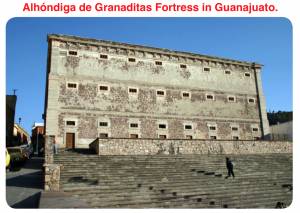

This city and it’s fortress were extremely important to Spanish colonial power. Guanajuato was the location of “Mina La Valenciana,” which was at that time one of the world’s richest silver mines. During the 100 years before Mexican Independence, over 60% of all silver production in the world as a whole came from “La Valenciana” in Guanajuato. Across Europe, it was Mexican silver that filled bank vaults to the ceiling.

This city and it’s fortress were extremely important to Spanish colonial power. Guanajuato was the location of “Mina La Valenciana,” which was at that time one of the world’s richest silver mines. During the 100 years before Mexican Independence, over 60% of all silver production in the world as a whole came from “La Valenciana” in Guanajuato. Across Europe, it was Mexican silver that filled bank vaults to the ceiling.

Precisely because the city was so essential to their economic power and survival, the Spanish kings kept their most well-armed and well-trained elite military forces posted in Guanajuato City, stationed at a military fortress called the “Alhóndiga de Granaditas.” It was there that the “Insurgentes” engaged Spanish colonial soldiers in a fierce battle. When it was over, the Insurgentes had secured the first significant military victory of the War of Mexican Independence at the “Alhóndiga de Granaditas.”

Inspired by their major victory in Guanajuato, the Insurgentes continued their revolutionary march to Mexico City. Led by Hidalgo and other insurgent leaders, the revolutionaries marched through the Mexican States of Querétaro, Michoacán, Estado de Mexico, Jalisco, Aguascalientes, Coahuila, and Chihuahua. Along the way the Mexican people responded to this call to fight for freedom from Spain, and soon, the Insurgentes had gathered a massive army of over 60,000 poor Indigenous people.

After numerous other victories the Insurgentes were ambushed. Hidalgo was captured and beheaded by the Spaniards on July 30, 1811. After Hidalgo’s execution, José María Morelos took command of the insurgent army. Morelos was a brilliant military leader, gaining 22 victories within nine months. Using guerrilla tactics, he won the liberation of most of Southern Mexico from Spanish oppression. Morelos then called together the first Mexican Congress, which soon after declared Mexico’s independence and drafted the first Constitution. Morelos was defeated and captured in 1815 by Spanish troops, who then executed him by firing squad.

For a time, elite Spanish forces regained control of Guanajuato. In an attempt to terrorize people and keep them from joining the ongoing rebellion, the heads of Hidalgo, Ignacio Allende, Juan Aldama, and José Mariano Jimenez (other revolutionary leaders) were hung from the outside four corners of the Alhóndiga de Granaditas fortress in Guanajuato City for ten years. Despite the widespread use of this kind of colonial terrorism, the Mexican people continued to resist, and finally, after years of fighting, they won the war in 1821 and Mexico formally proclaimed its independence from Spain.

This history is why El Grito de Dolores and “El 16 de septiembre” continue to be very important commemorations to all Mexicans. This is also why on every September 15th, even over 200 years later, we celebrate “El Grito de Independencia”:

¡Que Muera El Mal Gobierno! ¡Que Viva Mexico!

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla

Hidalgo was 57 years old when he became the initiator of the Mexican War of Independence. Even though he was poor, he was very well educated and was a priest and college professor. Padre Hidalgo was an expert on the French Revolution, and even spoke Nahuatl fluently.

The early morning of the 16th of September, 1810 he and Ignacio Allende decided to make the call for battle against the Spanish in the town of Dolores. From the church square the bells rang as he called out “¡Viva Nuestra Independencia!, ¡Viva América!, ¡Viva México! ¡Muera el mal gobierno!, ¡Mueran los gachupines!”

Since then we celebrate “el Grito de Independencia” also known as “el Grito de Dolores.”

Hidalgo is credited with raising the spirit of rebellion of Mexicans against oppression. Because of his patriotism, his championing of human rights, and his personal courage, he is considered “el padre de la Patria.”

Josefa Ortíz de Domínguez

is considered the maximum female leader of the War of Independence. She was born in the present day city of Morelia, Michoacán on March 19, 1771. She supported the struggle led by Hidalgo and from her home the Insurgentes organized the first rebellion against the Spanish.

José María Morelos y Pavón

José María Morelos y Pavón

He was a brilliant insurgent leader who started as a follower of Hidalgo. He was known as the “servant of the motherland.” He was born very poor on September 30, 1765 in Morelia, Michoacán (which was named in his honor). Morelos was of Indigenous and African descent.

A former priest, he later become the greatest military and political leader of the war of independence. After Hidalgo was assassinated, Morelos fought to liberate the states of Michoacán, Guerrero, Oaxaca, Puebla, Estado de México, Veracruz, and Morelos from Spanish control.

One of his well know statements was: “Que la esclavitud se proscriba para siempre y lo mismo la distinción de castas, quedando todos iguales y sólo distinguira a un americano de otro el vicio y la virtud.” – “May slavery be forever forbidden as well as the separation of our peoples by caste, thereby leaving all equal, and the only difference among one American and another shall be our vices and our virtues.”

Mariano Matamoros

He was also a priest and military leader, born in Mexico City on August 14, 1770. He was the right hand of Morelos. He fought and helped liberate the present day state of Morelos.

El Pípila

El Pípila

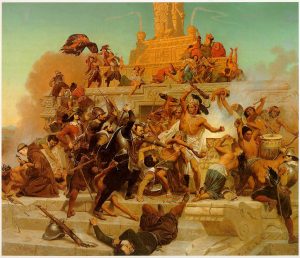

The first major victory of the Insurgentes against the Spanish forces was at the Alhóndiga de Granaditas fortress in Guanajuato City. This victory inspired others to join the insurrection. It was there that the Spanish colonial soldiers had locked themselves in after Hidalgo and 20,000 poor Indigenous Mexicans had surrounded them. It was the last stronghold of royal troops in Guanajuato.

The Insurgentes found it impossible to take the fortress until one poor mine worker named Juan José de los Reyes Martinez volunteered to bring down the main gate of the fortress on his own. Juan José, known among the other mine workers as el Pípila, was admired and respected for his unusual strength.

El Pípila lifted a massive stone onto his back, and thereby protected from Spanish gunfire, he picked up a torch with his other hand. Using the massive stone as a shield, he then walked up to the main gate of the fortress, and set it on fire. The gunfire of the Spanish colonial troops would just bounce off the stone. The main gate was burned and fell, and the insurgents took control of the fortress, and soon after that they took control of the entire city of Guanajuato as well.

Today this monument to El Pípila overlooks the city of Guanajuato. At its base it reads:

“Aun Hay Otras Alhóndigas Por Incendiar.”

“Even today there are other Alhóndigas we must burn.”

Vicente Guerrero

Guerrero was the son of an indigenous mother and African father. He was born in the present day state of Guerrero (named in his honor) on August 10, 1783. After all the other insurgent leaders had been captured and assassinated, Guerrero was the only one that continued to fight against the Spanish invaders.

– An Escuela Aztlan/ Somos Raza Youth Project Booklet for Political & Cultural Consciousness –

by H.L. Simón Salazar. Originally posted on 09/15/2017. Revised 09/11/2018, 09/14/2025.

.

This and other Escuelita Aztlan/ Somos Raza Political Education Histories are available as paper booklets and downloadable PDFs that can be printed and shared. All donations collected in the purchase of the booklets goes to fund the work of Somos Raza Youth Project & Unión del Barrio.

To order, visit us online at @UnionDelBarrio,

https://uniondelbarrio.org,

info@uniondelbarrio.org or call 619-398-6648