The Re-Orientation of the Movimiento and the Founding of Unión del Barrio

The Historical Context Of The Year 1981.

1981 was an extremely significant year for U.S. imperialism. It is be impossible to fully understand the rise of Ronald Reagan in 1981 without considering how the previous two decades of the 1960s and 1970s had dealt the U.S. one after another domestic and international crisis, humiliation, and defeat. During the 60s and 70s, the main trend in the world had been of mass movements for social justice, anti-war/ anti-establishment sentiment, domestic political assassinations, and a worldwide revolutionary fervor. U.S. imperialism was reeling as the 1970s began, and it was a decade that was proving to be equally as disastrous for the U.S. empire as the 1960s.

1981 was an extremely significant year for U.S. imperialism. It is be impossible to fully understand the rise of Ronald Reagan in 1981 without considering how the previous two decades of the 1960s and 1970s had dealt the U.S. one after another domestic and international crisis, humiliation, and defeat. During the 60s and 70s, the main trend in the world had been of mass movements for social justice, anti-war/ anti-establishment sentiment, domestic political assassinations, and a worldwide revolutionary fervor. U.S. imperialism was reeling as the 1970s began, and it was a decade that was proving to be equally as disastrous for the U.S. empire as the 1960s.

The 1970s were marked by important events such as the August 29, 1970 Chicano Moratorium March in East Los Angeles, the electoral victory of the socialist Salvador Allende and the Unidad Popular in Chile (September 4, 1970), the political victory of the Vietnamese revolution (January 23, 1973), the Watergate crisis and Nixon’s resignation (August 8, 1974), and serious domestic economic and fuel crises. The decade ended with the triumph of the Iranian Islamic Revolution (February 11, 1979), the triumph of the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua (July 19, 1979), the Iran Hostage Crisis (November 4, 1979), and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan (December 25, 1979). Demoralized and delusional, the political class of the United States felt overwhelmed in a sea of deception, corruption, social/ political/ economic crisis, and military violence, both within the U.S. and internationally.

Before he was president of the US, Ronald Reagan was a second tier buffoonish actor who had “named names” in collaboration with red-scare mccarthyism.

With the candidacy of Ronald Reagan for the presidency of the United States, the weakened North American empire had found a political buffoon that could act his way into being projected as the savior of its global imperial power. Throughout his presidential campaign, Reagan promised to set loose a domestic pullback of 1960s/1970s social programs, and a worldwide anti-Communist counter-revolutionary crusade, primarily against former colonial countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. Immediately after assuming the presidency on January 20, 1981, Reagan began to fulfill his campaign promises by dismantling many of the most progressive social programs within the U.S. Furthermore, he initiated a new escalation of the “cold war” – transforming it into hot wars throughout the world with direct political and/or military interventions. The Soviet Union was aggressively attacked as the “evil empire,” a new “arms race” was declared, and Latin America – especially Central America – was brought into the imperial cross-hairs. This represented a global counterinsurgency that was marked by the rise of what later became know as a the “Neocons” in Washington D.C.

Within the U.S., attacking and repressing progressive and liberation struggles had been coordinated through existing government projects such as COINTELPRO.[1] On the other hand, there was a buying off and “institutionalization” of many of the political and social demands of the movements, effectively neutralizing radical struggles for the transformation of society, and setting the foundation for what later would become the “non-profit industrial complex” – with non-profit organizations and NGOs seeking to do the work of radical or progressive political organizations, without the politics.

This was a dual strategy to de-politicize a period of global liberation struggle, and it helped bring about the decline and subsequent defeat of the Chicano Movement, a defeat that was virtually completed by the late 1970s. By 1981, independent community based struggle was almost non-existent in most barrios throughout Southern California, and only pockets of organized and politically motivated community struggle persisted.[2] As if to provide the formal declaration of the end of the Chicano Power movement, the U.S. federal government officially designated the 1980s as the “Decade of the Hispanic.” It was under these circumstances that Unión del Barrio was brought into being.

During The Summer Of 1981 Union Del Barrio Was Founded

Unión del Barrio was founded late in the summer of 1981, on August 29th, by a core group of veteran activists, with each individual having between ten to fifteen years of involvement in the struggle for raza self-determination. The first meeting was held at the home of Compañero Ernesto Bustillos in Barrio Logan, San Diego, and was attended by Jesse Constancio, Howard Holman, and Juan Parrino. Within weeks, this small group was expanded to include Jeff Garcilazo, Leticia Jimenez, Clemente Diaz, Catalina Diaz, David Rico, Marcelino Frias, Irene Cañedo, Liliana Garcila, Rico Pacheco, Luz Guillen, Geno Jimenez, Abe Suarez, and Rigoberto Reyes. Each of these camaradas came with many years of experience in barrio-based organizing. Together, this group was to form the first general membership of Unión del Barrio.

Unión del Barrio was founded late in the summer of 1981, on August 29th, by a core group of veteran activists, with each individual having between ten to fifteen years of involvement in the struggle for raza self-determination. The first meeting was held at the home of Compañero Ernesto Bustillos in Barrio Logan, San Diego, and was attended by Jesse Constancio, Howard Holman, and Juan Parrino. Within weeks, this small group was expanded to include Jeff Garcilazo, Leticia Jimenez, Clemente Diaz, Catalina Diaz, David Rico, Marcelino Frias, Irene Cañedo, Liliana Garcila, Rico Pacheco, Luz Guillen, Geno Jimenez, Abe Suarez, and Rigoberto Reyes. Each of these camaradas came with many years of experience in barrio-based organizing. Together, this group was to form the first general membership of Unión del Barrio.

The key reason for establishing Unión del Barrio was that its founding members saw an absence of a multi-issue, politically militant organization that was willing to utilize and improve upon the tactics used in the late 1960’s and early 70’s; tactics which brought to our communities the few advances we did win, such as bilingual education, Chicana/o Studies, affirmative action, college financial aid, the hiring of raza in areas previously closed to us, etc. The founding members of UdB felt that a militant multi-issue organization was needed to organize large sectors of our community and provide direction on the many problems facing us. Issues such as barrio violence, police brutality, political and economic power, and the re-building of the movement would thereby be the focus of the newly founded Unión del Barrio.

The Separation from the CCR

Several core-founding members had held leadership positions in the Committee on Chicano Rights (CCR), and had recently left the CCR primarily because it limited most of its work around a single issue – immigration. Although the founding members of UdB always considered immigration an important issue, it did not square with the type of multi-faceted political work they felt was urgently needed.

Several core-founding members had held leadership positions in the Committee on Chicano Rights (CCR), and had recently left the CCR primarily because it limited most of its work around a single issue – immigration. Although the founding members of UdB always considered immigration an important issue, it did not square with the type of multi-faceted political work they felt was urgently needed.

Their leaving the CCR was never seen as an organizational “split.” Although the founding members of UdB had fundamental differences as to the direction of the movement, they respected the history and activism of the CCR, especially its chairman Herman Baca. There was a conscious effort at that time (an effort that continues into the present) not to publicly criticize the CCR, as this would be used by the system as a way of confusing our gente and placing a wedge between our organizations and supporters. From its inception Unión del Barrio believed that the best way we could prove ourselves correct and worthy of respect within the community and the movement was primarily through our concrete work in our barrios and our everyday political consistency.

Identifying Who We Were And What We Wanted

At the initial meeting in August of 1981 our founding members identified several issues that needed to be addressed immediately. These were the development of a name, logo, statement of purpose, and points of unity for the organization. Of course these basic elements of UdB would be influenced by the history, ideals, and images of the Chicano Power movement of 1965 to 1975. Even the date of our founding, August 29, 1981, was directly inspired by the anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium of 1970. Moreover, they discussed how to present and promote this new organization to the community as a whole, under conditions that were very different from the previous period of struggle.

While deciding on what to call the new organization, our founding members were looking for a name that represented the conditions of our struggle and what they wanted to accomplish. They chose the name “Unión” because they understood that the great majority of our raza were working class people, and we wanted to carry on the tradition of labor organizing. They also agreed on its use because the word represented “unity,” something that was (and is) desperately needed within the movement. The word “Barrio” was included in our name because most of the membership lived in the barrio, and they wanted to ensure that the organization was always to be rooted in the community. The founding members of UdB had seen how too many Chicano Movement activists had taken on “middle class” values, and had maintained little or no relationship to the community, had lost the “pulse of the barrio,” and suffered from a limited understanding of the real conditions within which our people actually lived.

The discussion at the first meeting of UdB then focused on the image that would best represent our organization. They wanted something that connected us to our past as a people and a movement – something that could be at the same time historical and representative of militant action. They embraced the Mexica (Azteca) “Caballero Aguila,” primarily because it symbolized our indigenous history of struggle. The order of the Caballero Aguila was among most highly trained warrior formations within the Mexica army, and they were the last defenders of Tenochtitlán (then capital of the Mexica nation) against the Spanish invasion led by Hernán Cortez in the year 1519. The important figure of Cuauhtémoc belonged to this particular military order, and it was his legacy that has come to be represented by the eagle headdress that the founding members of UdB selected as our organizational icon. Finally, they considered the fact that some of the most important formations of our movement had eagles (or other birds) as a part of their organizational symbols – the United Farmworkers (UFW), Crusade for Justice, La Raza Unida Party, CCR, etc. UdB wanted to carry on the historical legacy of those who had sacrificed and struggled before us.

There was also discussion as to what colors we would use as a part of our symbol. After some discussion on the subject we agreed to use red and black. This decision was based on the fact that in Latin America red and black represented labor struggles as well as revolutionary organizations, and the unity between these struggles. These were also the colors most used by many organizations of the Chicano Movement.

Formulating The Founding Principles Of Unity And Building An Organization Of Organizers

The founding members of Unión del Barrio had backgrounds in the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan (MEChA), the United Farm Workers (UFW), the Brown Berets, La Raza Unida Party, the Chicano Park Steering Committee, and had been influenced by Chicano Movement organizations such as the Crusade for Justice, and CASA (Centro de Acción Social Autonoma). It was this extensive background in the Chicano Movement that linked the last period of struggle of the 1960s and the early 1970s, to the founding of UdB in 1981. Our founding members envisioned rebuilding what had been the best characteristics and victories of the Chicano Movement, and improving upon its errors.

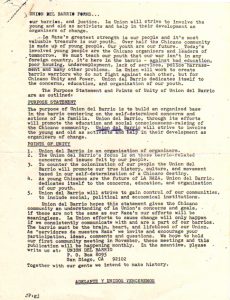

The August 29, 1981 public announcement of the founding of Unión de Barrio.

The following is an excerpt from the original September 1981 document announcing the formation of Unión del Barrio:

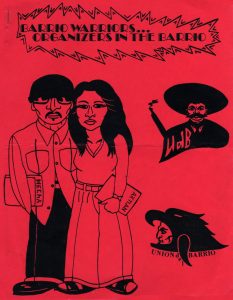

“Unión del Barrio Forms… La Union will strive to involve the young and old as activists and help in their development as organizers of change… La Raza’s greatest strength is our people and it’s most valuable treasure is our youth. Over half the Chicano community is made up of young people. Our youth are our future. Today’s involved young people are the Chicano organizers and leaders of tomorrow. We must teach our youth that our war isn’t in any foreign country; it’s here in the barrio – against bad education, poor housing, underemployment, lack of services, police harassment and many other problems. La Unión will work to create barrio warriors who do not fight against each other, but for Chicano Unity and Power. Unión del Barrio dedicates itself to the concerns, education, and organization of our youth.

“The purpose of Unión del Barrio is to build an organized base in the barrio centering on the self-determined concerns and actions of la familia. Unión del Barrio, through its efforts will promote the education and social consciousness-raising of the Chicano community. Unión del Barrio will strive to involve the young and old as activists and help in their development as organizers of change.

POINTS OF UNITY

- Unión del Barrio is an organization of organizers.

- The Unión del Barrio’s focus is on those barrio-related concerns and issues felt by our people.

- To counter the colonization of our people the Unión del Barrio will promote our true history, culture, and movement, based in our self-determination of a Chicano destiny.

- As young Chicanos are the future of LA RAZA, Unión del Barrio dedicates itself to the concerns, education, and organization of our youth.

- Unión del Barrio will strive to gain control of our communities, to include social, political, and economic institutions.

“Unión del Barrio hopes this statement gives the Chicano community an understanding of La Unión’s concerns and goals, if these are not the same as our Raza’s our efforts will be meaningless. La Unión’s efforts to cause change will only happen if we consistently communicate with and are a part of our barrios. The barrio must be the brain, heart, and lifeblood of our Union. As ‘servidores de Nuestra Raza’ we invite and encourage your participation, ideas, comments, and questions. We hope to hold our first community meeting in November [1981], these meetings and this publication will be happening monthly… Together with our gente we intend to make history.

ADELANTE Y UNIDOS VENCEREMOS.”[3]

In this spirit, at the first meeting the founding members of Unión del Barrio outlined this general political program that included who we were and what we wanted. In addition to the program, the discussions focused on several characteristics they did and did not want the organization to embody.

They were all critical of the “caudillo” style of struggle that was common during the Chicano Movement. They agreed that an organization that depended on one personality for leadership was bound to encounter serious problems and would be impossible to sustain over time. History had proven that the strengths and weaknesses of the “caudillo” would be the strengths and weaknesses of the organization. When the leader decided to call it quits or was neutralized by the state, the organization would inevitably be destroyed. Thus, our founding members stressed the need for building an “organization of organizers,” where everyone would be accountable and no one person would be irreplaceable.

Our Communities Were The Priority

The founding members of Unión del Barrio were also critical of those individuals and/or organizations that claimed to represent our communities, but primarily involved themselves in liberal causes that were not concretely related to the priorities of our communities. UdB also considered it an error for people to support self-determination and revolution in Mexico, Central America. and/ or Palestine, but openly refuse and reject the self-determination of millions of raza here, within the current borders of the United States. Moreover, too many activists would spend time organizing cultural events and festivals, while consistently drawing the line and refusing to deal with important questions such as economic exploitation, police/ migra terror, violence in the barrios, and self-determination for our gente here in Aztlan. There was an agreement that UdB would take on a role of setting an example of organizing around political principles – we wanted to build an organization that would focus primarily on barrio-based issues, yet be guided by a vision and understanding that we were part of a struggle for the self-determination and liberation of our gente.

The founding members of Unión del Barrio were also critical of those individuals and/or organizations that claimed to represent our communities, but primarily involved themselves in liberal causes that were not concretely related to the priorities of our communities. UdB also considered it an error for people to support self-determination and revolution in Mexico, Central America. and/ or Palestine, but openly refuse and reject the self-determination of millions of raza here, within the current borders of the United States. Moreover, too many activists would spend time organizing cultural events and festivals, while consistently drawing the line and refusing to deal with important questions such as economic exploitation, police/ migra terror, violence in the barrios, and self-determination for our gente here in Aztlan. There was an agreement that UdB would take on a role of setting an example of organizing around political principles – we wanted to build an organization that would focus primarily on barrio-based issues, yet be guided by a vision and understanding that we were part of a struggle for the self-determination and liberation of our gente.

We also recognized that a fundamental problem facing our communities was the lack of political and cultural consciousness. We agreed that UdB would promote at all times the real history and political realities of our communities. We wanted to return culture to its most important historical role – as a liberating culture – versus being used as a tool for the system to pacify communities in the face of oppression.[4]

We also understood, although at different degrees among the different founding members, that our national struggle was fundamentally a class struggle, and that colonialism, capitalism, and imperialism were the fundamental enemies of our people. While there was no doubt that we were anti-capitalist since our founding, as UdB we had seen how self-declared “socialist” or “leftist” multi-national organizations had embraced opportunism and/or turned their backs on our communities. Often these ideologically “radical” multinational organizations preached revolution, but did very little to organize radical politics in their own white communities. Often, they found it easier to come into our barrios and places of work to tell Mexicans how we should liberate ourselves, and they would aggressively attack groups like UdB, La Raza Unida Party, and the CCR as “narrow-nationalist” and counter-revolutionary. For some of those groups, UdB members were ideologically backward. Many self-anointed revolutionaries argued that we would first have to give up our history as a people, surrender our claims to the land, and set down our Mexican and Latin American flags, and only then could we be considered true “internationalists” and “comrades”. These “radicals” believed their task was to educate us about the minimum requirements for their kind of “socialism” that they were seeking to construct within a happy multicultural U.S.A.

UdB rejected these tendencies, and later would refer to them as “kkkommunists”.[5] The negative practices of these and other organizations, in addition to the reactionary violence of the state against any struggle that identified itself as “socialist,” pushed many movimiento activists away from the ideals of socialism, and this was reflected within Unión del Barrio at the time of our founding since more than one of our founding members held anti-communist prejudices. In spite of this ideological limitation, we still identified our fight as a struggle against capitalism and colonialism, although during this period we did not promote terms such as socialism or communism.

As a consequence of these early internal ideological struggles, Unión del Barrio was incorrectly identified by some “socialist” organizations as anti-communist, and/ or incapable of understanding dialectical struggle. This of course was not true. Yet, we understood our organizational priority as rooted in the need for re-building and uniting the few groupings that were at that time still involved in barrio-based struggle, and we did not prioritize the inevitable internal debate regarding socialism. We understood that the Chicano Movement had been destroyed not because it had been socialist, but because it was for la raza, and that the scattered, disunited, and sometimes misdirected resistance that survived would not be sufficient to defend the interests of our people. The legacy of our movement needed to be recovered and UdB sought to advance political unity in general – not only within our communities – but our communities were our priority above all else.

As a consequence of these early internal ideological struggles, Unión del Barrio was incorrectly identified by some “socialist” organizations as anti-communist, and/ or incapable of understanding dialectical struggle. This of course was not true. Yet, we understood our organizational priority as rooted in the need for re-building and uniting the few groupings that were at that time still involved in barrio-based struggle, and we did not prioritize the inevitable internal debate regarding socialism. We understood that the Chicano Movement had been destroyed not because it had been socialist, but because it was for la raza, and that the scattered, disunited, and sometimes misdirected resistance that survived would not be sufficient to defend the interests of our people. The legacy of our movement needed to be recovered and UdB sought to advance political unity in general – not only within our communities – but our communities were our priority above all else.

Building upon the victories of the Chicano Movement, while at the same time exposing opportunist “hispanismo” that had come to define the 1980s, Unión del Barrio provided to the movimiento a foundation of resolute and independent barrio-based militancy that had almost been completely wiped out. Nonetheless, during the first three years of our existence, Unión del Barrio was primarily a local San Diego “mass-based” formation with broad principles of unity, it was loosely structured, and maintained limited accountability over our membership. UdB meetings functioned in an “ultra-democratic” fashion, under “robert’s rules of order”, and extraordinary efforts were made to encourage all general members to hold leadership positions and speak publically on behalf of the organization, regardless of their political development. Initially this looseness proved to benefit the organization because people were challenged to grow politically, although it soon led to contradictions that could only be resolved as the organization progressed and evolved.

The Chicano Nationalism of Unión del Barrio: An Ideology To Live By

Clearly, during this period our political vision was somewhat vague and still needed to be developed. Yet, it was this vision that represented the three political tendencies found within Unión del Barrio at that time:

Clearly, during this period our political vision was somewhat vague and still needed to be developed. Yet, it was this vision that represented the three political tendencies found within Unión del Barrio at that time:

– Progressive reformism, which we identify as an idealist view which wanted to make the system more receptive to la raza, without changing the economic/cultural/social realities and conditions of Mexicanas/os, nor struggling for a fundamental change within U.S. capitalist society.

– Progressive nationalism, which called for raza self-determination within the context of existing U.S. institutions/ society, and was generally critical of capitalism and imperialism, but did not accept socialism as an alternative.

– Revolutionary nationalism, which in its earliest form included the ideals of “progressive nationalism” although took it a step further and called for the establishment of Chicano Mexicano based socialism throughout Aztlan.

Together these tendencies represented a form of “Chicano Nationalism” that can be identified as the ideological foundation of UdB between 1981 and 1983. Throughout this period, the organization was loose enough that these tendencies did not openly contradict each other. For the first three years of our existence we attempted to combine, reconcile, and develop these three tendencies until 1984, when revolutionary nationalism became the central political foundation guiding the strategy and tactics of Unión del Barrio. In a UdB working document written to serve as an ideological guide, we summed-up our political vision as follows:

“The political involvement and experiences of Unión del Barrio membership has led us to an essential conclusion: for our people to break the historical bonds of oppression and exploitation we must self-determine… our own destiny through Chicano Nationalism… The dominant Anglo society has structurally denied us our true political and cultural history. This denial [of our history] is consciously committed as an attempt to hide the vicious Yanqui take over and continuing subjugation of Aztlan, México, and Latin America… Unión del Barrio recognizes Chicano Nationalism as the only legitimate avenue for achieving Chicano Liberation… For the Chicano, nationalism means the survival and growth of culture; our right to social, political, and economic self-determination; and the right to control our land of Aztlan… Chicano Nationalism does not claim superiority over other nationalities, but it does demand equality. Chicano Nationalism must be used to direct our daily and future activities, both as individuals and as an organization…”.[6]

It must be repeated that the early 1980s was a period of powerful right-wing attacks and international counter-insurgency. The presidency of Ronald Reagan had unleashed a wave of reactionary attacks throughout Aztlan and the world. In other words, it was the survival of our struggle that was fundamentally important during this period.

Yet, even during these early stages, our political line represented a seed of a political program that would enable us not only to survive but also grow tremendously. As years passed, our basic Chicano nationalism fused with our strong roots in the community, our unwavering commitment to defending the interests of our gente, the honesty and selflessness of our membership, and the experiences gained during the Chicano Power period of 1965-75. Together these elements allowed Unión del Barrio to come to terms with our strengths and weaknesses, made us open to learning from the political views and experiences of other organizations and revolutionaries worldwide, and allowed us to visualize true social, political, and economic change for our gente.

Roots In The Community And Adherence To National Liberation Were The Keys To Survival As An Organization

During our first stage of development we placed a heavy emphasis around ending barrio youth violence. Numerous “end barrio violence” conferences and marchas were organized, and we worked directly with at least five barrio youth groups – for example the “Lowrider Car Club Council,” “Las Unicas,” “Sherman Unidos,” “Stylistics” and “the Originals.”

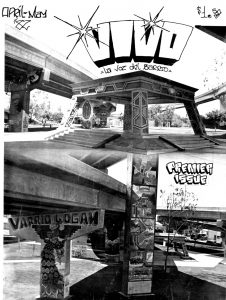

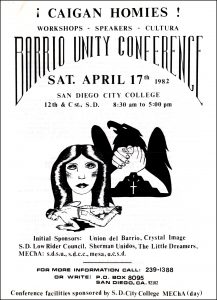

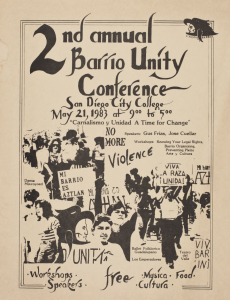

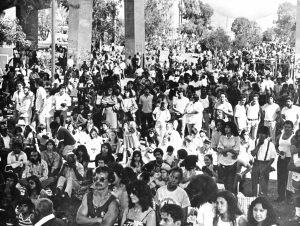

Furthermore, we played a significant role in the publication and distribution of Vivo Magazine, and our first Barrio Unity Conference was held at San Diego City College on April 17, 1982, co-organized with the above mentioned groups. That first Barrio Unity Conference was a tremendous success, and over 400 community people from 22 different barrios came together to discuss the questions of education, culture, legal defense, barrio organizing, and their relationship to raza self-determination.[7] It became an annual event, and in 1983 over 500 people participated in the conference.[8] This work truly exemplified the commitment UdB maintained in relation to the community in general, and to barrio youth in particular.

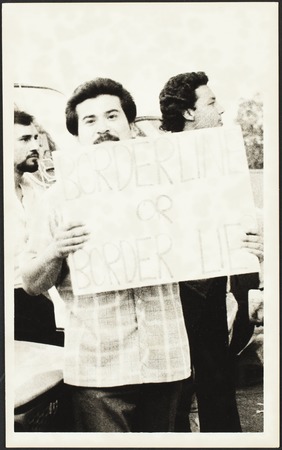

During this period UdB went through one of the first major political struggles since its formation. This political struggle centered around the San Diego “Street Youth Program.” Contradictions materialized when UdB refused to support this program because of its collaboration with the police department and San Diego mayor at the time, Pete Wilson. These contradictions prompted UdB to publish a statement opposing the tracking of barrio youth, and our position led to a public split with the “Street Youth Program.” UdB upheld our view that self-determination struggle required non-collaboration with the state and/or law enforcement, and that this was the only possible path to follow if we hoped to end end barrio violence. Although it was a difficult position to take, and one that motivated efforts to isolate and undermine the work of UdB in our communities, it was an important struggle, and served to strengthen the principled unity and political maturity of Unión del Barrio.[9]

While social service agencies cooperated with “law enforcement” as a way of ending barrio violence, Unión del Barrio resisted police violence, called for community control over the police, and continued to organize conferences and marchas calling attention to both police and migra brutality. These events exposed the fact that police were using barrio violence in our communities as a pretext for harassing raza, and that law enforcement created a militarized and hostile environment for all young people within our barrios. In a statement developed for the 2nd Annual Barrio Unity Conference in 1983 we explained: “The… abusive conduct of the various police agencies… are nothing less than a war declared on the Chicano Mexicano residents of San Diego County…”.[10]

From Consistent Activism And Historical Awareness Came Our Political Schooling

It was also during this first stage of development that we began to re-appropriate the historic symbols and events of the Chicano Movement as central to our community work. For example, in 1982 we organized the “12th Commemoration of the Chicano Moratorium of August 29, 1970”, the “16th de Septiembre” at Chicano Park, and in 1982 published community outreach material with the image of Benito Juárez.

In early 1982 we set into motion a type of activity that led to tremendous political growth within Unión del Barrio – the Barrio Forums. These monthly foros were organized in different barrios throughout San Diego on an ongoing basis, and served as a political school for our membership as well as the community in general. The first Barrio Forum was held on December 1, 1982 and focused on the question of Chicano Studies. We found that these activities provided political education around other issues such as U.S. intervention in Central America, the need for community control over schools, and the role of multinational corporations in the oppression of raza and other oppressed nationalities.

For these events we would invite leading political, academic, and cultural figures such as Rudy Acuña (respected Chicana/o Studies professor and author of Occupied America), Ernesto Vigil (former co-chair of the Crusade For Justice), Jose “Dr. Loco” Cuellar (professor and musician), Xenaro Ayala (from La Raza Unida Party), Arnulfo Casillas (co-founder of Voz Fronteriza, Si Se Puede, and other publications) and many other individuals, as well as organizations such as Voz Fronteriza, VIVO Magazine (a progressive barrio-lowrider publication), the Coalition To End Barrio Violence, CADENA, CISPES (Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador), DIA (Draft Information Alliance), La Raza Unida Party, and numerous M.E.Ch.A.’s.

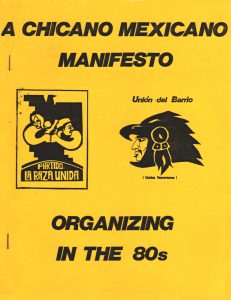

Our relationship with La Raza Unida Party (also known as Partido Nacional La Raza Unida – PNLRU) became very important during this period. With LRUP we initiated an “Encuentro” process that would last several years through which we debated the most urgent issues of our movement. It was in late 1983 that a combined effort between LRUP and UdB published “A Chicano Manifesto: Organizing in the 80s.” This 27-page booklet included numerous political analyses from both groups, for example: “Towards Unity Building in the 80’s,” “Against White Chauvinism – Towards Chicano Liberation and International Solidarity,” “Somos Chicano Mexicano,” “Position Paper: Raza Youth Work,” and “The Importance of Grassroots-Barrio Based Organizing.”

Our relationship with La Raza Unida Party (also known as Partido Nacional La Raza Unida – PNLRU) became very important during this period. With LRUP we initiated an “Encuentro” process that would last several years through which we debated the most urgent issues of our movement. It was in late 1983 that a combined effort between LRUP and UdB published “A Chicano Manifesto: Organizing in the 80s.” This 27-page booklet included numerous political analyses from both groups, for example: “Towards Unity Building in the 80’s,” “Against White Chauvinism – Towards Chicano Liberation and International Solidarity,” “Somos Chicano Mexicano,” “Position Paper: Raza Youth Work,” and “The Importance of Grassroots-Barrio Based Organizing.”

Learning How To Deal With Political Isolation During the Early 1980s

It was also in this first stage of development that we gained the experience of working within coalitions. Our first actual coalition work was when we helped form CHISPA (Chicanos In Solidarity with the People of Central America) in late 1983. It was a “broad based” coalition that included the Chicano Federation, Chicano Moratorium Committee, M.E.Ch.A. Central of San Diego, and CISPES (Coalition In Solidarity with the People of El Salvador). The work within CHISPA was as successful as it was important, and in 1983 we were able to organize a marcha in support of the Salvadoran struggle with the participation of over 500 people. Later, again through CHISPA, UdB helped organize a cultural program that was attended by over 400 people and published several issues of a newspaper titled CHISPA. This work was done as part of a coordinated effort to support the FMLN and the liberation struggle of our raza in El Salvador. It was this kind of practical experience that enabled us to differentiate between progressive and reactionary elements, and time and time again, allowed us to break the many attempts – both by the state and reactionary forces claiming to be part of our movement – to slander, isolate, and neutralize Unión del Barrio.[11] In this sense, our unconditional solidarity with Central American struggles was extremely important because it lent a revolutionary spirit to Unión del Barrio that offset the political reformism and assimilationist tendencies that had captured many community organizations under the banner of the “decade of the Hispanic.”

In addition to our work in support of Centroamérica, UdB kept active in other sectors of community work. The tremendous activism of Unión del Barrio during the first half of 1983 included over 20 different activities, ranging from pickets, marchas, rallies, and fundraising events. During the summer of 1983 we wrote “…for the last two years [1981 and 1982], La Unión has played a key role in the liberation struggle of the Chicano Mexicano people. In Aztlan, there are probably not more than one or two organizations that have been as active as the Unión or consistently provided our gente involvement in self-determination activities. Through the Unión’s organizing efforts [such as] the conferences, marchas, demonstrations, barrio forums, speaking engagements, and outreach to other Raza activists in Aztlan, we have served as a role model providing our Raza with political alternatives. The alternative of sincere politics, self-respect for Raza, and true liberation from gringo controlled politics.”.[12]

In addition to our work in support of Centroamérica, UdB kept active in other sectors of community work. The tremendous activism of Unión del Barrio during the first half of 1983 included over 20 different activities, ranging from pickets, marchas, rallies, and fundraising events. During the summer of 1983 we wrote “…for the last two years [1981 and 1982], La Unión has played a key role in the liberation struggle of the Chicano Mexicano people. In Aztlan, there are probably not more than one or two organizations that have been as active as the Unión or consistently provided our gente involvement in self-determination activities. Through the Unión’s organizing efforts [such as] the conferences, marchas, demonstrations, barrio forums, speaking engagements, and outreach to other Raza activists in Aztlan, we have served as a role model providing our Raza with political alternatives. The alternative of sincere politics, self-respect for Raza, and true liberation from gringo controlled politics.”.[12]

Despite our ideological and structural weaknesses, by the end of 1983 Unión del Barrio had become the one of the most active movement organizations throughout Aztlan. Through practical barrio-based work, UdB was able to concretely show how our socio-economic condition was not based on some reluctance or inability of la raza to better our condition. The real problem was (and is) a system built upon colonialism, imperialism and capitalism. More precisely, since its founding, Unión del Barrio has challenged the false front of “democracy” continuously fed to our communities within the United States, exposing this parasitic system as dependent on keeping our people and other oppressed peoples undereducated, unskilled, disorganized, and politically powerless.

The founding members of UdB were conscious of the fact that the future held many uphill battles and that the path of raza liberation struggle would be long and difficult. Exactly what the future held, obviously they didn’t know, but they did know that they were embarking on a protracted struggle for liberation. At the tenth anniversary of the founding of our organization, Juan Parrino, a founding member of UdB, summed-up the feeling of some of the people present at the first meeting of 1981:

“…It’s hard to believe the… years that have passed since a handful of activists gathered in the backyard of a Logan Heights home and began the formation of Unión del Barrio. In all honesty, and I have never shared these recollections before, I remember a feeling of great expectation that August evening in 1981. A profound sense of self-determination pulsed through me. I felt as if our coming together to form Unión del Barrio would amount to something far more significant than the sum of our previous contributions to raza struggles… We had come together to help rebuild the Chicano Liberation Movement, and set the stage for heightened Raza Resistance. We were departing from an organization that primarily focused on a single issue and organized from a human rights mode. We set out to create an effort that would help regenerate Chicano Mexicano Nationalism, and instill the fighting spirit of Raza Self-determination so necessary for attacking the multitude of issues affecting the Chicano Mexicano Nation…”.[13]

[1] COINTELPRO was short for “Counter Intelligence Program” and was launched by the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover to disrupt and destroy the different social, political and anti-war movements that had developed across the United States during the 60s and 70s. COINTELPRO was especially aggressive and violent against the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement (A.I.M.). Later these same tactics were used against organizations that declared solidarity with the liberation struggles in Central America.

[2] The Crusade for Justice, PNLRU, MLN-M.

[3] See original UdB organizational announcement, September of 1981.

[4] See “Victory is A Process Which Begins With Concientización,” Education, Chicano Studies, and Raza Liberation, La Verdad Publications, 1983.

[5] The term “kkkommunist” came from the African People’s Socialist Party, an organization that influenced UdB beginning in the mid-1980s. Our relationship with the APSP is described in greater detail in subsequent chapters of this book.

[6] “Chicano Nationalism: An Ideology To Live By”, winter 1981.

[7] See Unión del Barrio Newsletter, June 1982.

[8] See May 23, 1983 Los Angeles Times article “500 Chicanos Rally To Signal New Awareness”.

[9] See Unión del Barrio Newsletter, June 1982, “Position Statement on the Street Youth Program” and the April-May issue of Vivo Magazine. Include more information about this struggle.

[10] Unión del Barrio Press Release, June 23, 1983.

[11] See “A Brief History of Unión del Barrio Coalition Work,” ¡LA VERDAD!, July-Aug 1989.

[12] “Unión del Barrio 1983 Update,” July 1983.

[13] See Advancing The Chicano Mexicano Movement, Juan Mexicuauhtli Parrino, La Verdad Publications, February 1993

—————————————

GO TO NEXT SECTION (1984 to 1986).