“LEST WE FORGET!”

Committee on Chicano Rights (Reprinted & Updated from UCSD Herman Baca Archives)

I still vividly remember what happened to me personally and politically in Los Angeles, California on August 29, 1970. Thirty thousand Chicanos from throughout the U.S. marched in the streets to protest and call for an end to the war in Vietnam. A war, much like Afghanistan today, that was destroying our most precious heritage… our youth. On that day, a police riot ensued and Los Angeles Times Reporter Ruben Salazar, along with citizens Angel Diaz and Lynn Ward were killed. Numerous persons were wounded and hundreds were jailed by the L.A. Police and Sheriff’s Department, including national Chicano leader, Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales. By 1965, President Lyndon Johnson had declared Vietnam a police action. Dark and foreboding war clouds were present in every Chicano barrio throughout the Southwest. While many young white males received college deferments, white controlled draft boards systematically recruited poor people, blacks and especially Chicanos in record numbers to fight the war in Vietnam. At the time, Chicanos comprised 6% of the nation’s population, but were 20% of the wars causalities. Many of my own friends served and died in Vietnam.

THE CHICANO COMMUNITY:

After five years of the war, reality finally hit the Chicano community. Young Chicanos were dying in obscene numbers and ‘body bags’ were being returned to the homes of grieving families throughout the U.S. The Chicano Movement recoiled in anger and called for protests against the government’s policy of sending its young people to die in foreign wars. The movement’s political position had always been that the white, racist system had made Chicanos strangers in their own land by placing them last in jobs, education and rights, while placing them first to die in its wars. In the early stages of organizing the Moratorium, a ‘generational’ divide arose within our community over the movement’s anti-war position. Bitter discussions and arguments occurred within our own families. Strong opposition to the anti-war position came mainly from the men we admired and looked up to most; our grandfathers, fathers, uncles and older brothers. There had always been a long tradition of military service within the Chicano community. Many had proudly served with distinction (my own father included) and died in World War II and Korea. In fact, Mexican Americans are the most decorated and have won the most medals of honor of any ethnic group in the U.S. To the men of those generations (who had never been political), service in the military equated to a kind of ‘machismo.’ The older generation could not understand why, if we were men we did not want to enlist or serve in Vietnam. However, as the war wore on and casualties increased, many of the same veterans began to understand and support our anti-war position.

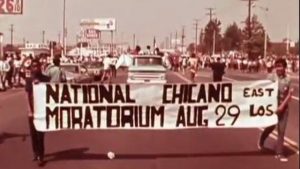

THE MORATORIUM:

At its onset, the moratorium demonstration was planned as a peaceful protest seeking redress from the U.S. Government based on rights supposedly protected and guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights. On Saturday August 29, 1970 I & three individuals arrived in Los Angeles around 7:00 A.M. As we gathered, I witnessed something I had never seen before. Thousands upon thousands of Chicanos from all over the U.S., many from New Mexico, Texas, Colorado, Arizona, and the Midwest all taking part in a political event. From San Diego alone, one thousand people attended the demonstration. At the time the demonstration was the largest protest organized by Chicanos in their 130 years history as a conquered people in the U.S. The march started late that very hot day. When the march started, people rallied behind banners of the Virgin De Guadalupe, MAPA, Brown Berets, MEChA, Crusade for Justice, UFW, etc. Along the route, people yelled words of encouragement & many joined the procession. After five long miles, we finally arrived at Laguna Park (now Salazar Park).

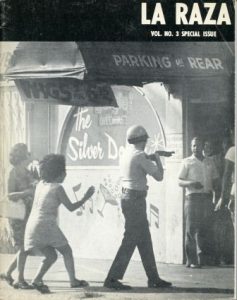

THE POLICE RIOT:

Sitting down in the park, we heard a commotion and saw police coming from the direction that we had just left. Suddenly, we saw police advance on the peaceful crowd without any provocation. The majority of the crowd at the front of the demonstration had absolutely no idea what was happening. As the police advanced, I witnessed scenes that I will never forget; hundreds of our people children, women, young, and old all being beaten, tear gassed, maimed, and arrested. The police and sheriff deputies appeared to be totally out of control. They seemed crazed with a desire to hurt, maim and kill Chicanos. Chicanos witnessing the attack stood up in self-defense and fought back. I remember at one point, the bright August sky turning black because of the large number of objects being thrown back at the police. People protected themselves by throwing bottles, cans, sticks, dirt; any object they could get their hands on. For a while, the crowd appeared to have the upper hand. Two or three times, they pushed the police back. However, soon the police regained control. At that moment, I learned a political lesson I’ve never forgotten. Even though there were only hundreds of police and thousands of Chicanos, the police had something we lacked; organization. As I stood in the park amidst the litter, police began lining up in formation, waiting for something to happen. I soon found out what they were waiting for, a change of the wind direction. Suddenly, tear gas canisters were landing 3 or 4 feet from me. As the canisters hit the ground, everyone began to retreat. Most of us had no idea where we were. We started to walk with hundreds of other people down Whittier Blvd. While walking, we saw undercover police coming out from the sides of the streets with guns drawn and shooting into the sky, and then at the crowd. A Good Samaritan asked if we needed a ride and drove us to the Mexican American Political Association headquarters where MAPA State President Abe Tapia and Bert Corona held a press conference to denounce the police’s actions. Around 6:30 P.M. we finally departed to San Diego. I remember looking back, seeing East Los Angeles burning!

LONG YEARS HAVE PASSED:

For many, the political question still remains: Has anything really changed socially, economically or politically for our people? Obviously some things have changed; we are no longer the ‘sleeping giant.” We are not the forgotten, invisible, or silent minority. In fact, Chicanos will soon be the largest ethnic group in the United States. Numerous individuals serve in state sponsored positions as politicians, Ph.D.’s, professors, principals, counselors, students, etc. Yet despite all these ‘cosmetic’ changes, the majority of people of Mexican ancestry in the U.S. in 2017 face more difficult lives (under Nazi Donald Trump’s race baiting hating anti-Mexican administration) than in 1970. Consider, today more of our youth are in prisons than colleges! We still face the problems of police brutality, high unemployment, unemployed and under-educated youth, inadequate housing and a lack of medical care. We still face hundreds of deaths at the U.S./Mexico border. There are still gross violations of our peoples human & civil rights. After 47 years, the struggle for equality has not ended & continues.

HISTORICAL LESSONS:

- To me (personally) the Chicano Moratorium was a defining moment in my life. To people of Mexican ancestry the demonstration provided a valuable political lesson that in 2017 we seem to have forgotten. We learned as a people that problems like the Vietnam War (1970) & today’s white supremacists/nationalists (Donald Trump & his ilk) that are threatening our rights can only be confronted, stopped & defeated by the historical principle of self-determination.

- Again on August 29, Chicanos in San Diego & thru out Aztlan will again commemorate the Chicano Moratorium. A historical day that Chicanos will remember & more importantly remind today’s generation that if social, economic & political changes are to be made; they must build on history & go forth with the same spirit, sacrifice and struggle as their predecessors in 1970.

-END-

Updated by UdB, August 28, 2018.