Since the founding of Unión del Barrio in 1981, educators have played a central role in the evolution of the organization. Evidence of this is how compañero Ernesto Bustillos, the principal founder of Unión del Barrio, worked as a teacher for the majority of his life, and was among the original founders of the Association of Raza Educators (ARE). Even today, a significant percentage of Unión del Barrio membership remains connected in some manner to the educational sector, not only as faculty, but also as staff and students. The history of Unión del Barrio as well as our current community work clearly represent why May 15, “Día del Maestro” continues to hold a special significance for our membership.

Since the founding of Unión del Barrio in 1981, educators have played a central role in the evolution of the organization. Evidence of this is how compañero Ernesto Bustillos, the principal founder of Unión del Barrio, worked as a teacher for the majority of his life, and was among the original founders of the Association of Raza Educators (ARE). Even today, a significant percentage of Unión del Barrio membership remains connected in some manner to the educational sector, not only as faculty, but also as staff and students. The history of Unión del Barrio as well as our current community work clearly represent why May 15, “Día del Maestro” continues to hold a special significance for our membership.

Yet, we should keep in mind that this tradition of educators and political struggle is not something that appeared overnight, nor is it unique to Unión del Barrio. There is a long and rich legacy of teachers involved in struggle throughout Nuestra América – this is particularly true in México.

Escuela Normal Rural de Ayotzinapa

The rural teachers school of Ayotzinapa is an important part of this legacy. Incredibly, revolutionary teachers like Lucio Cabañas Barrientos – founder of El Partido de los Pobres, Genaro Vázquez Rojas – founder of La Asociación Cívica Nacional Revolucionaria, and Othón Salazar Ramírez – founder of Movimiento Revolucionario del Magisterio, were all trained in the Escuela Normal Rural de Ayotzinapa. This history is an important part of the why we must never forget the 43 missing students of Ayotzinapa. Further north, Arturo Gámiz García also contributed to this legacy, working as a revolutionary teacher and founder of Grupo Popular Guerrillero in the Mexican state of Chihuahua.

These are just a few examples of the thousands of revolutionary teachers that have served and struggled for the betterment of our communities. Today it is easy to develop a long list of compañeras and compañeros who every day work in the educational sector, only to continue working after regular hours as “agents of social change.” Every May 15th we should remember and honor these exceptional educators, and work to emulate their commitment to the people and their spirit of struggle.

Within the current context of cultural decay and unrestrained violence, it is important to remember that there was a time when Mexico had one of the best systems of public education in the world. Educational content was openly socialist, prioritized the interests of working class, and challenged young people to work for a better world, instilled intellectual curiosity, and promoted international solidarity. Of course,this system of public education only worked because of the heroic struggle and sacrifice of teachers.

The following is a brief history describing the Mexican roots of our tradition of “liberatory education” that too many people have forgotten, and helps confirm the revolutionary role teachers in México have played historically and continue to fulfill in the present…

Educational Martyrdom

by Edgar González Ruiz, translated by La Verdad Publications

The May 15th remains part of a national civic calendar emerging from the Mexican Revolution of 1910, in spite of the current efforts by the Mexican right-wing that has risen to power to try and eliminate this part of history.

[In México] “El Día del Maestro” was formally established in 1918 under the premise that teachers had been a decisive factor in the progress of the nation, and because teachers were among the first to join the revolutionary movement of 1910.

During the Cristero War that took place in México from 1926 to 1929, the clergy opposed secular [non-religious] education and secularism in general. Consequently, many teachers were persecuted by the Cristeros, and they renewed their attacks in the following decade.

In 1935 President Lázaro Cardenas ordered that every year, May 15th would be a civic holiday and the names of 10 martyrs of education should be read aloud.

On May 15, 1935, President Lázaro Cardenas presided over a ceremony in honor of those teachers killed or “desorejados” by Cristeros. Cardenas ordered that every year, May 15th would be a civic holiday and the names of 10 martyrs of education should be read aloud. [Short of killing them, Cristero rebels would often cut teachers ears and or nose off as a way to keep them out of pueblos and stop them from educating their children. Female teachers would also have their breasts cut off.]

At that time, attempts to implement a socialist teaching curriculum and the basic elements of sex education in public schools led groups of religious fanatics to initiate a violent backlash. They destroyed schools and textbooks, they murdered, mutilated and viciously attached teachers, especially in rural areas.

Over time, too many people have lost this memory of those teachers killed. While at the same time the inheritors of Cristero ideology have come to power throughout México, and for decades resources from the national treasury and educational system [as well as the media] have promoted the Cristero cult as an heroic and persecuted movement.

The hatred that the right-wing government professes against the history of public education in México is also extended against those people who work in public education in the present. Consequently, it is all the more important that we remember and commemorate the names of those teachers killed by Cristero fanaticism.

Maria Rodriguez Murillo

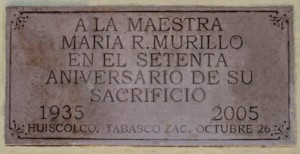

During the morning of October 26, 1935, the Cristeros warned the rural teacher Maria Rodriguez Murillo to leave the village [of Huiscolco in Zacatecas]. When she refused, she was raped, beaten, tied from her feet with a rope and dragged behind a galloping horse down the dirt road leading out from Huiscolco. Thereafter, the Cristeros cut off [Maestra Rodriguez’s] breasts, and hung them on the brush located along the sides of the road, one on the right side, and one on the left side. This was done to send a message to other rural teachers that they would not be allowed to provide their children a “socialist” education (see David Raby, Education and Social Revolution in Mexico, p. 137 , Salvador Frausto Crotte, “Mistress Maria R. Murillo – victim of bigotry and religious hatred”, El Universal, June 17, 2001).

So was the assassination of the teacher Maria Rodriguez Murillo. She was a dedicated teacher who worked in Huiscolco, Zacatecas. The morning after the bloody murder, the local priest offered mass in the town church and absolved the murderers of any wrong-doing.

Ms. Murillo had been accused of being a communist, and she had been condemned for supporting the re-distribution of land to the poor. The vast majority of the clergy condemned land reform, and agrarian campesinos who received land during those years were threatened with eternal punishment in hell.

[Before her assassination] Murillo had confronted the cacique of the village because he refused to allow workers to learn to read and write. Soon after, the local priest attacked her as a heretic for seeking to promote literacy.

Carlos Toledano

During this same period in the region of Tlapacoyan near Altotonga, Veracruz, the Cristeros committed numerous similar atrocities. According to Indalecio Sáyago, a Mexican politician who at that time was a rural teacher: “…landowners, ‘white guards,’ hoarders of farm products, and priests all united and organized the fiercest campaign against educational workers.

Female teachers were raped and their breasts cut off, other male teachers had their ear removed and/or were killed. It was during that period when a group of ‘white guards,’ during the middle of the day and in broad daylight, surrounded the schoolhouse where the teacher Carlos Toledano was teaching class to his students. The fanatics bound Maestro Toeldano’s hands and feet with barbed wire, and positioned him in the middle of his classroom. Using the classroom furniture, papers and books as fuel, they surrounded the teacher and lit a fire, burning him alive in front of his students.”(Miguel Baltazar Vazquez Altotonga, a town with history, Altotonga, Veracruz, 2005, p. 231-32).

The martyrs of Teziutlán

November 15, 1935, in Teziutlán, Puebla, under the Cristero slogan of “¡Viva Cristo Rey! three rural teachers were killed in their schools and in the presence of their students:

Carlos Hernandez in the village of La Legua,

Carlos Pastrana Jiménez in the village of Ixtipan, and

Librado Labastida Navarrete, in the village of San Juan Xiutetelco.

All evidence indicates that the Cristeros planned to kill them at the same time, as well as to kidnap another female teacher, Nieves Gonzalez, age 20, who was taken and violently attacked. In a written declaration of war against educators, the Cristeros boasted of killing these teachers:

“…We must highlight the fact that (local Cristeros) have definitively and severely punished several corruptors of children. With the support of [government] tyranny, these perverts had been developing unspeakable tasks against our children. The names of these so-called ‘teachers’ are: Librado Labastida from the Santiago School, in the municipality of Xiutetelco; Carlos Sayago from La Legua School, and Carlos Pastrana, who was serving in the rural school of Ixtipan. Each of them have been killed, and their names are stamped here, so their shame can be forever remembered… “(Consuelo Reguer, God and my right, Volume 4, Jus, Mexico, 1997, p. 532).

Every year in Teziutlán a ceremony is held to remember the martyrdom of these teachers, and three commemorative plaques have been installed in the center of town to honor their sacrifce.

Micaela and Enriqueta Palacios

In the Guadalajara main offices of Section 47 of the National Union of Education Workers, a mural was installed named “In honor of the martyrs of education.” The work was completed on December 7, 2007 by Maestro David Carmona, positioned along with a memorial plaque with the names of teachers killed or mutilated by Cristero rebels.

For decades, workers from the public education sector have worked to institute efforts to honor these martyrs for education, and had initiated plans to build a monument to them in Guadalajara. This plan was abandoned in 1995 with the arrival of the National Action Party to power throughout that region.

The commemorative plaque in the SNTE headquarters describes the experiences of Micaela and Enriqueta Palacios, assaulted on November 19, 1935. The press at the time reported on the terrible abuses that these teachers suffered when a group of rebels attacked the school in the village of Camajapita (in the Highlands of Jalisco).

“The victims reported that at approximately 11:00 p.m. a group of rebels appeared and (…) violently snatched the girls’ father and tied a rope around his neck. Meanwhile the teachers suffered numerous types of abuse and humiliation. At that point the assailants threatened the family. They made is clear that if they remained in the village or continued the ‘game’ of providing their children with a socialist education, they were willing to return and kill them. Immediately after issuing this threat, and ignoring the cries and unhappy laments of the family, the rebels unsheathed a large knife and proceeded to cut one ear from each of the teachers and their father, provoking heavy bleeding… Before leaving, the rebels burned textbooks and destroyed the furniture and doors of the school. ”

Vicente Escudero: High School Hero

Vicente Escudero, barely 16, was a student of the Rafael Donde High School Number 7. As a result of his high academic achievement in school, in 1934 he was nominated to fulfill the role of volunteer rural teacher.

That same year he moved to the town of Santa Mónica de Viudas, in Valparaíso, Zacatecas. He moved there to develop his educational work, but soon fell victim to the hatred of the Cristeros, who accused him of being a communist and atheist.

On April 5, 1934, seventy Cristeros arrived at his home while the young teacher was getting ready to go to teach classes. He was dragged out of his home, and the attackers cut off the skin from the soles of his feet, then they cut open his knees. Bloodied and with tears in his eyes, Vicente was then stoned and hung from a tree. The fanatics justified this attack because they considered Vicente to be the “anti-Christ” since his presence had offended the Church.