PART TWO of THREE

We Disagree With The Decision To Change What M.E.Ch.A. Stands For – Both In Name And In Principle

Unión del Barrio respects the organizational autonomy of MEChA, though we always retain the right of independent criticism and political analysis. What took place at the 2019 National MEChA Conference in Los Angeles is historically significant and of broad interest to movimiento forces in general. Consequently, we are compelled to publish our own report and analysis.

Unión del Barrio disagrees with the decision to change what M.E.Ch.A. stands for – both in name and in principle – and respectfully suggests that ME(ChA) consider revising the April 5, 2019 National ME(ChA) statement by foregrounding a self-criticism for the poorly planned and executed discussion and vote on the name change. We also suggest that ME(ChA) consider convening a new process that includes a broader analysis of “Chicanx de Aztlan”; provides space for participation from a greater number of MEChA chapters that are affiliated with the national structure; and invites input from independent MEChA chapters, MEChA alumni, and independent community organizations.

Unión del Barrio disagrees with the decision to change what M.E.Ch.A. stands for – both in name and in principle – and respectfully suggests that ME(ChA) consider revising the April 5, 2019 National ME(ChA) statement by foregrounding a self-criticism for the poorly planned and executed discussion and vote on the name change. We also suggest that ME(ChA) consider convening a new process that includes a broader analysis of “Chicanx de Aztlan”; provides space for participation from a greater number of MEChA chapters that are affiliated with the national structure; and invites input from independent MEChA chapters, MEChA alumni, and independent community organizations.

We applaud MEChistas who are willing to engage in constructive struggle to overcome contradictions that exist within the organization, and who challenge individuals who demonstrate reactionary behavior within particular chapters of MEChA. Ongoing criticism/self-criticism has always been an important tenet of organized political struggle, within specific organizations and within the movimiento as a whole. For decades our organization has engaged in exactly this type of struggle. Through internal debates and ongoing community work, we prioritize constructive criticism/self-criticism in order to address and combat reactionary nationalism, machismo, and homophobic/transphobic behavior, etc. We expanded our Political Program to reflect these collective changes, while advancing the leadership of mujeres, LGBTQ+, and disabled comrades within our political culture and our daily practice on the streets of our barrios. Furthermore, we did so while privileging the daily struggles of our working class communities, and always promoting solidarity with liberation struggles throughout Nuestra América and the world. Unión del Barrio is far from perfect, but we highlight this process of criticism/ self-criticism to explain what motivates our critique of the recent MEChA name change.

We state unequivocally that our criticisms are not personal attacks against any individual MEChista, and we have no interest in participating in personalized social-media “take-downs.” Our nearly 40-year legacy of uninterrupted community-based liberation struggle is ample evidence that Unión del Barrio is a serious organization, and that we have nothing to gain from social media “call-outs” of any one generation, chapter, or member of MEChA. Instead, the criticisms we have collectively decided to publish focus on challenging colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism through a raza-liberation lens that is rooted in daily community-based struggle. We challenge what we see as incorrect political arguments/practice, and we reserve the right to critique manifestations of neoliberal political culture that misdirect the attention and limited resources of our movimiento away from resisting increasingly vicious attacks against la raza. There are three reasons why Unión del Barrio disagrees with the MEChA Name change:

- The debate was incomplete and the vote was poorly executed.

- The underlying rationale behind the rejection of “Chicanismo” demonstrates a clear anti-Mexican bias.

- The political concept of Aztlan emerged from the Chicano Movement of the 1960s-70s, not just from MEChA.

1. The Debate Was Incomplete And The Vote Was Poorly Executed

2019 marks the 50th anniversary of MEChA. The legacy of 50 years of struggle belongs not only to current MEChistas, but also to MEChA alumni and to generations of raza activists who took risks and sacrificed themselves in order to break down the educational walls that the racist U.S. ruling class had built around our communities. MEChA means so much to so many people. There must have been some awareness that making a drastic change to what MEChA stands for would be controversial, and would generate a substantial negative reaction among current MEChA members, MEChA alumni, and community organizations. Therefore, prioritizing this debate was at best poorly considered, especially within the current context of trumpista fascist violence unleashed against our communities, including state-sponsored terror (ICE raids, family separations, military deployed to the border, etc), acts/threats of white nationalist violence, dehumanizing political discourse from all levels of government, imminent U.S. invasions across Nuestra América, intensified exploitation of our labor, environmental degradation, etc.

As far as we know, the only substantive analysis made on the topic was a document titled “Reflections on Aztlán and its Role in the Chicanx Student Movement” that was officially shared on the National MEChA conference social media account. That document made a highly critical argument challenging the concept of Aztlan. No counter-analysis that was supportive of Aztlan was ever shared. As far as we know, there was no substantive analysis done on the significance of “Chicanismo” either. Instead, the term was dismissed because it “…directly translates to Mexican-American, [and] is exclusionary…” No academic literatures that expressed support for the history or legacy of the concepts of Aztlan or Chicanismo were cited. No requests were made to community organizations who are still connected to the concepts asking them to clarify their position. No alumni were invited to provide input into this very important discussion. Instead, a resolution was verbally introduced and voted on during the final hours of the final day of the 2019 National Conference that was originally intended to commemorate the 50th anniversary of MEChA. Finally, the 29 votes cast in favor of the name change represent less than half of the approximately 60 chapters currently affiliated to the National MEChA structure, and far fewer than the hundreds of independent chapters on colleges and high schools across the U.S.

As far as we know, the only substantive analysis made on the topic was a document titled “Reflections on Aztlán and its Role in the Chicanx Student Movement” that was officially shared on the National MEChA conference social media account. That document made a highly critical argument challenging the concept of Aztlan. No counter-analysis that was supportive of Aztlan was ever shared. As far as we know, there was no substantive analysis done on the significance of “Chicanismo” either. Instead, the term was dismissed because it “…directly translates to Mexican-American, [and] is exclusionary…” No academic literatures that expressed support for the history or legacy of the concepts of Aztlan or Chicanismo were cited. No requests were made to community organizations who are still connected to the concepts asking them to clarify their position. No alumni were invited to provide input into this very important discussion. Instead, a resolution was verbally introduced and voted on during the final hours of the final day of the 2019 National Conference that was originally intended to commemorate the 50th anniversary of MEChA. Finally, the 29 votes cast in favor of the name change represent less than half of the approximately 60 chapters currently affiliated to the National MEChA structure, and far fewer than the hundreds of independent chapters on colleges and high schools across the U.S.

Unión del Barrio disagrees with the decision to change what M.E.Ch.A. stands for because it will not help correct any of the contradictions described by supporters of the name change. In fact, it has become abundantly clear that the March 31st vote has exacerbated contradictions that do indeed exist within our communities, such as intergenerational disunity (evident in the disrespect between current and elder MEChistas), narrow-nationalism (the resentment expressed between our people of Centroamérica and Mexico), as well as gender and sexual identity bias (distrust among mujeres/ hombres/ raza who identify as LGBTQ+). If by changing the name of MEChA some people hoped to bring about more unity and inclusivity, then clearly they have been proven wrong because MEChA is not more united.

2. The Underlying Rationale Behind The Rejection Of “Chicanismo” Is Anti-Mexican.

The April 5, 2019 statement released by the new National ME(ChA) Board includes the following text:

We encourage individuals to continue to celebrate their Chicanidad within the organization, but without the exclusion of our other Latinx hermanxs who don’t identify with that. Since MEChA must be a place for Latinx people to find community in higher education, we wish to use our name to reflect that… Chicanx, which directly translates to Mexican-American, is exclusionary. Although some identify with the political connotations Chicanx can have, it has not traditionally been used in that way. We recognize that it would be wrong to force non-Mexican-Americans, Indigenous Mexicans who cannot identify with this term, and Black Mexicans whom this term has historically excluded to use this term to describe their political philosophy. As it is, MEChistx members who are not Mexican-American are often victims of xenophobia from Chicanx MEChistxs, and Indigenous and Black MEChistxs are often subjected to anti-Indigenous and anti-Black violence by Mestizx Chicanx MEChistxs… We are by no means erasing those struggles; on the contrary, we are acknowledging and addressing the oppressive history and nature of MEChA…

The underlying rationale behind the rejection of Chicanismo is deeply flawed and demonstrates a clear hostility to the history and the very nature of MEChA that is rooted in the Chicano movement of the 1960s-70s:

- It presumes a direct causal link between Chicanismo and xenophobia, “anti-Indigenous and anti-Black violence”, “Mexican-centrism”, Mexican hegemony, etc.

- It discredits and invalidates any use of Chicanismo by people who are not of Mexican heritage.

- It considers it “wrong” to impose “Chicanx” on people who do not identify with that term, but presumes universal acceptance of “Latinx”.

- It denigrates or erases the leadership of current and/or historical protagonists who broadly identified themselves as Chicanas, Chicanos, Raza, people of Mexican heritage, etc.

- It narrowly, incorrectly, and unilaterally defines “Chicanx” as “directly translat[ing] to Mexican-American” and therefore deems it as “exclusionary.”

By dropping “Chicanx” to promote the symbolic inclusion of Indigenous, Central American, African, and LGBTQ+ raza in 2019, this rationale advances a form of inclusion via dispossession – it seeks to center “other” raza by wiping away the collective identity of a people’s 50-year history of struggle. Intentionally or not, this act of symbolic inclusion erases the very real participation of Indigenous, Central American, African, and LGBTQ+ raza who fulfilled leadership roles within the 1960s-70s movement, and who continue to identify with Chicanismo in the present, of which there are many. We know that there was no malicious intent among the majority of MEChistas who voted to support the name change, or who felt there was a need to make the organization “more inclusive.” Yet there was a vocal sector within the name change advocates who confirm this generalized anti-Mexican and anti-Chicana/o/x bias in favor of the now fashionable “Latinx”.

There are some MEChistas who do not agree with the philosophy of the organization, its name or political orientation. It is unprincipled to join an organization and then try to completely change the character of that organization, especially one that has a half century of history and hundreds of thousands of alumni. Whatever the public motivations that supported dropping “Chicanx de Aztlan” from MEChA might have been, that line of reasoning more closely aligns with the anti-Mexican attacks that are the daily bread of trumpista fascism. What happened in Los Angeles on March 31st was a “woke” demonstration of trumpism because it was able to dissolve the 50-year legacy of MEChA struggle much more efficiently than the ongoing attacks against MEChA by the Alt-Right. Brown “woke-splaining” does not value collective struggle, and clearly aligns with an agenda that has culminated with the erasure of 50 years of independent raza-led community-student struggle, that was rooted in the Plan de Santa Barbara and the legacy of MEChA. People who harbor an anti-Mexican, anti-Chicana/o/x bias should reconsider their membership in an organization they are not aligned with philosophically.

There are some MEChistas who do not agree with the philosophy of the organization, its name or political orientation. It is unprincipled to join an organization and then try to completely change the character of that organization, especially one that has a half century of history and hundreds of thousands of alumni. Whatever the public motivations that supported dropping “Chicanx de Aztlan” from MEChA might have been, that line of reasoning more closely aligns with the anti-Mexican attacks that are the daily bread of trumpista fascism. What happened in Los Angeles on March 31st was a “woke” demonstration of trumpism because it was able to dissolve the 50-year legacy of MEChA struggle much more efficiently than the ongoing attacks against MEChA by the Alt-Right. Brown “woke-splaining” does not value collective struggle, and clearly aligns with an agenda that has culminated with the erasure of 50 years of independent raza-led community-student struggle, that was rooted in the Plan de Santa Barbara and the legacy of MEChA. People who harbor an anti-Mexican, anti-Chicana/o/x bias should reconsider their membership in an organization they are not aligned with philosophically.

The same applies to reactionary narrow nationalists who would exclude raza from Central and South America or any potential comrades who choose to participate in an organization or movement. We acknowledge that there have been contradictions in MEChA chapters and that some people have been pushed away from the organization because they are not Mexican, but that type of reactionary behavior is limited, and in no way representative of the dominant values of MEChA. Anyone who seeks to exclude another person from participating in MEChA for not being Mexican/Chicana/o/x should be sanctioned, and if they refuse to acknowledge the contradiction, they should be expelled. We also know that MEChA has historically taken strong positions in support of the people’s struggles in Ho Chi Minh’s Vietnam, the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua, the Farabundo struggle in El Salvador, revolutionary Cuba, AIM, the liberation struggle in Palestine, against apartheid in South Africa, and many more. For these reasons, we reject the argument that MEChA is by its very nature anti-Black, anti-Central American, or anti-Indigenous.

If the intention was to move MEChA away from “Mexican-centric” behavior, then there must be substantial barrio-based work to raise conciencia and support real international solidarity and ideological unity across Nuestra América – work that would otherwise prioritize stopping the coup and invasion of Venezuela, ending the blockade against Cuba, overturning the colonial domination of Puerto Rico, exposing the imperialist manipulation of Central American migrants, and blocking the capitalist devastation of our planet. To support struggles of Indigenous raza, one should prioritize support for the American Indian Movement (AIM), support the NO Dakota Access Pipeline (NoDAPL) struggles, and always uphold the fundamental right for self-determination of indigenous peoples as central to our political programs. At the 2019 National MEChA Conference some of those urgent debates were tabled, in favor of advancing a name change to promote a more symbolic form of “inclusivity”.

Some MEChistas argue that MEChA is intrinsically “anti-LGBTQ+.” We know that the heavy religiosity of our communities continues to propagate homophobia and transphobia. However we believe that today, MEChA is one of the best spaces for our sisters, brothers, and gender non-conforming compas to participate in community struggle, to have their voices heard, and to hold leadership positions. This is evident in the current leadership who are openly LGBTQ+, and by the many workshops, caucuses, keynote speakers, and resolutions that have made MEChA a much more inviting space for all people. Erasing “Chicanx de Aztlan” will not eradicate hateful tendencies from the most backward members of MEChA; continuing to educate and raise conciencia among our gente is the only viable solution to overcome these reactionary tendencies.

3. The Political Concept Of Aztlan Emerged From The Chicano Movement Of The 1960s-70s, Not Just From MEChA.

The April 5, 2019 statement released by the new National ME(ChA) Board also included a summary of the rationale for removing “Aztlan”:

As a collective, we recognize that the term Aztlán reflects MEChistxs’ appropriation of Aztec cultures and traditions; however, many of our ancestors were not Aztec but rather Maya, Purépecha, K’iche’, Guaraní, Garifuna, among others. The use of the term ‘Aztlán’ also influences us to take part in the erasure of Indigenous peoples who are the true ancestral stewards of the US Southwest. We voted to remove ‘Aztlán’ because although Aztlán was created as a philosophical ideology, it has had geographical consequences in claiming the land that was taken by the US on February 2, 1848 with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Chicanxs from the ’60s claimed the Southwest part of the United States as ‘Occupied Mexico’ and our rightful land; however, this is not our land. The reality is this land belongs to the many Indigenous people who were here before the Mexicans and Chicanxs, e.g. the Diné people, the Tongva people, etc… We acknowledge… the founding documents of the organization… Although we share some of its values, in the current moment we must strongly condemn White Supremacy, Anti-Blackness, Queer-antagonism, Trans*-antagonism, ableism, Anti-Indigenous Sentiment, Mexican centrism, anti-Central American sentiments, and the colonial concept of Aztlán. We must continue to evolve as a national organization in light of our ever-changing political reality in order to better serve Latinx students.

The underlying rationale behind the rejection of Aztlan is also deeply flawed and demonstrates a revisionist inclination in favor of European colonialism and U.S. imperialism:

- It presumes a direct causal link between the concept of Aztlan and “White Supremacy, Anti-Blackness, Queer-antagonism, Trans*-antagonism, ableism, Anti-Indigenous Sentiment, Mexican centrism, anti-Central American sentiments…” and even “colonialism”

- It invalidates the land question that has been central to all of our struggles since 1492.

- It unilaterally marks “Mexicans and Chicanxs” as non-indigenous, presumably closer to European colonizers.

- It is ironically inconsistent, first by claiming to champion indigenous identities, and then by presuming the universal acceptance of “Latinx” – a term fundamentally rooted in European colonialism and U.S. neoliberal cultural imperialism.

- It ignores that the idea of Aztlan predates Aztec (Mexica) culture, is deeply intertwined with the history of the Hopi and Anasazi peoples, and that Nahua culture was deeply intertwined with all other Indigenous groups – by language, trade, spirituality, migration, blood, and most importantly, anti-colonial resistance.

- Some MEChistas cited the “Reflections on Aztlán and its Role in the Chicanx Student Movement” document to suggest the completely reactionary comparison of Aztlan to Zionism and the illegal settler state of Israel. For obvious reasons, equating to Zionism the use of Aztlan within the name of MEChA demonstrates the most backward form of revisionism.

“Aztlan” is not an instrument of colonial power, it was and continues to be a political concept that was part of a community based response to the denigration of la raza, a proclamation of indigenous pride, and a call for self-determination born of liberation struggle. Aztlan is a conceptual shield to defend all of our communities from reactionaries who argue that “we are all illegal aliens” on this land. It is a political-historical touchstone that reminds us that our ancestors did not cross an ocean to arrive to these lands. Aztlan is less about a specific territory as it is a banner of liberation struggle against colonial subjugation and imperialist intervention. Aztlan is one conceptual link in an unbroken chain of indigenous peoples struggles that extend back in time to the resistance of the Anasazi, the Lakota, and the defense of La Gran Tenochtitlan, to Machu Picchu, and to the Mapuche – a continental struggle from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego embodied in the symbolism of the eagle and the condor. Aztlan also embodies the shining examples of Toussaint L’Ouverture and Dessalines burning to the ground the defenders of African enslavement, by any means necessary.

“Aztlan” is not an instrument of colonial power, it was and continues to be a political concept that was part of a community based response to the denigration of la raza, a proclamation of indigenous pride, and a call for self-determination born of liberation struggle. Aztlan is a conceptual shield to defend all of our communities from reactionaries who argue that “we are all illegal aliens” on this land. It is a political-historical touchstone that reminds us that our ancestors did not cross an ocean to arrive to these lands. Aztlan is less about a specific territory as it is a banner of liberation struggle against colonial subjugation and imperialist intervention. Aztlan is one conceptual link in an unbroken chain of indigenous peoples struggles that extend back in time to the resistance of the Anasazi, the Lakota, and the defense of La Gran Tenochtitlan, to Machu Picchu, and to the Mapuche – a continental struggle from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego embodied in the symbolism of the eagle and the condor. Aztlan also embodies the shining examples of Toussaint L’Ouverture and Dessalines burning to the ground the defenders of African enslavement, by any means necessary.

Aztlan is a both a conceptual legacy of native resistance as well as a physical homeland for a displaced indigenous struggle that has been on the front lines fighting European colonialism and imperialism for hundreds of years. It is intended to represent our historically rooted and righteous legacy of struggle that nourishes our fight for land and liberty, in the present. If a sector within the current leadership of ME(ChA) maligns these historical links as “colonial”, then all we can say is that they do not have the authority to break that chain. We know that some MEChistas want to change “Aztlan” to “Abya Yala” to represent the entire continent. We see and understand the logic behind that. But to propose such a change, it should be recognized that MEChA also belongs to the hundreds of thousands of MEChistas from who the current leadership inherited the organization, and there should be an honest effort to consult with these “forerunners in order to honor them.”

A Wake Up Call For MEChA Alumni

For alumni, the results of the 2019 National Conference should be a wake up call. There exists a terrible lack of participation and continuity in the movement that has had a direct impact on the current state of MEChA. Considering the 50-year history of MEChA, there are tens, if not hundreds of thousands of MEChA alumni across the U.S. who are now workers, educators, political figures, etc. Many have detached themselves from community struggle, and/or have not continued their support for MEChA in decades.

The void of mentoring and political guidance that MEChA alumni have collectively failed to provide to current MEChistas is too often being filled by agents of the Democratic Party, college administrators, careerist academicians, a growing number of campus-based student resource centers designed to de-radicalize working class students, employees from the 501c3 non-profit industrial complex, and social media “influencers” who are more committed to building their online profiles than community organizing. If MEChA alumni aren’t currently involved in political struggle (especially within the context of trumpista fascism), we are not now nor will we ever be in a moral position to blame current MEChistas for being co-opted by the system. Unión del Barrio urgently calls upon the hundreds of thousands of MEChA alumni, who over the last 50 years gained political conciencia and a love for our communities while they were members of MEChA, to step back into active political life! We invite those former MEChistas to join Unión del Barrio and become members of a political organization that will fight against capitalism, for the liberation of our peoples, and will stand in principled internationalist solidarity with oppressed peoples around the world. Only in this way can we provide a living, viable example for today’s MEChistas.

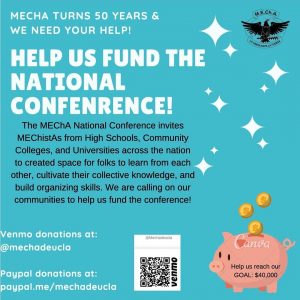

Alumni need to fulfill a role as “elders” who are both respectful and respected among the current generation of MEChistas. And for those who claim to be way too busy to get involved, we hope they can at least send consistent donations to current MEChistas (especially from MEChA de UCLA who are still in need of funds to pay for the 2019 Conference – make donations directly to their Venmo account <@mechadeucla> or PayPal <@mechadeucla>). MEChA alumni should not shirk this responsibility, especially within the current context of Trumpista fascism that has in its crosshairs every one of our communities and everything we fought for during the last 50 years.

Alumni need to fulfill a role as “elders” who are both respectful and respected among the current generation of MEChistas. And for those who claim to be way too busy to get involved, we hope they can at least send consistent donations to current MEChistas (especially from MEChA de UCLA who are still in need of funds to pay for the 2019 Conference – make donations directly to their Venmo account <@mechadeucla> or PayPal <@mechadeucla>). MEChA alumni should not shirk this responsibility, especially within the current context of Trumpista fascism that has in its crosshairs every one of our communities and everything we fought for during the last 50 years.

This Can Be A Unifying Call To Action And Self-Defense

MEChA alumni and community members have the right to voice our opposition to the name change, though many have done so in a negative fashion while personalizing the issue. We urge those criticizing the name change to do so in a political and constructive way, and not use derogatory language against current MEChistas that you may disagree with politically.

However, we will not be apologetic about being Mexican, Chicana/o/x, Central American, Indigenous, African, LGBTQ+, etc. We have every right as a people to be proud of who we are. We should not be expected to change our language, culture, the way we dress, the way we speak, or give up our history in order to be recognized among our peers. Nor should we demand others do the same in order to conform to a neoliberal ideal of “inclusivity.” We have every right to remember the anti-colonial character of our struggle to free ourselves from Spanish colonialism; to expel the French invaders; the fight against U.S. imperialism; to rise up as an indigenous people for Tierra y Libertad. Our African sisters and brothers have every right to fight against our common oppressors as members of the Black Panther Party, the African People’s Socialist Party, or Black Lives Matter, and we support them in principled unity. Conversely, we too have the right to have our own organizations like MEChA, La Raza Unida Party, and Unión del Barrio.

In the 50 years that MEChA has existed, it has produced a significant number of productive and progressive community members that should not be ignored in this process. Without community input, MEChA would be cutting its connection to the barrio based struggles which are the root of its existence.

Because many members of Unión del Barrio are MEChA alumni, we genuinely care about the wellbeing and political direction of the organization. Many of our members are teachers who are also advisors and mentors to current MEChistas. We have presented dozens of workshops at MEChA Statewide conferences, high school conferences, and National Conferences. Furthermore, we have called on community members and alumni to support MEChA instead of attacking current MEChistas.

We urge MEChistas to re-engage with our communities. MEChA should refocus, prioritize, and re-center community-based struggle to make it the heart and soul of every MEChA chapter, while pushing back against the dominant role of esoteric/neoliberal academic, 501c3, administrative/institutional political rhetoric and values. Academics, non-profits, and student services directors need to be asked to stay in their lane, unless they are willing to publicly privilege the community ahead of their personal economic and professional goals. When MEChA commits itself to defend communities, it can break the institutional dependency of the organization, and it inoculates itself against social media “woke-tivism” by disqualifying the political influence of individualists and opportunists who seek personal gains as online “influencers,” but never do anything real in the service of any of our communities. MEChA should welcome and honor non-academic people from community collectives and working class people from our barrios by speaking with working class community people, and avoid unintelligible “woke-splaining” and/or policing people’s use of language outside of campus-based activist bubbles.

We urge MEChistas to re-engage with our communities. MEChA should refocus, prioritize, and re-center community-based struggle to make it the heart and soul of every MEChA chapter, while pushing back against the dominant role of esoteric/neoliberal academic, 501c3, administrative/institutional political rhetoric and values. Academics, non-profits, and student services directors need to be asked to stay in their lane, unless they are willing to publicly privilege the community ahead of their personal economic and professional goals. When MEChA commits itself to defend communities, it can break the institutional dependency of the organization, and it inoculates itself against social media “woke-tivism” by disqualifying the political influence of individualists and opportunists who seek personal gains as online “influencers,” but never do anything real in the service of any of our communities. MEChA should welcome and honor non-academic people from community collectives and working class people from our barrios by speaking with working class community people, and avoid unintelligible “woke-splaining” and/or policing people’s use of language outside of campus-based activist bubbles.

Every one of us is more deeply connected to centuries of liberation struggle that is indigenous to these lands – a legacy that reaches back in time prior to the existence of any colonial/imperial universities, colleges, and high schools, prior to the establishment of the United States, or any settler colonial nation-state. Acknowledging this, after a university and college experience, raza students should return to our barrios to continue to organize and build better realities for our communities. Anything short of centering and prioritizing the self-defense of our communities is to cede space to trumpista fascism.

Unión del Barrio Values Criticism/Self-Criticism

Since our founding in 1981, Unión del Barrio has prioritized the process of critically assessing the strengths and weaknesses of the movimiento in order to correct collective errors, and thereby build upon positive aspects of the movement that fueled the political victories of the 1960s-70s. Since 1981 we understood that the movimiento had both victories and errors, but we never doubted the inherent importance of our collective history, nor did we reject the cumulative legacy of our people’s liberation struggles in Aztlan and throughout Nuestra América.

Evidence of our openness to critical forms of political struggle can be seen as far back as 1983 when, in unity with La Raza Unida Party, a number of “encuentros” were convened to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the Chicano Movement of the 1960s-70s. Out of these discussions Unión del Barrio developed and published a June 1986 document titled “Summing Up The Last Period: The Chicano Movement 1965 to 1975”. We delineated some key problems of our movement during that period – such as the lack of political development and revolutionary ideology, the role of the “white left,” the lack of discipline and organization, and the counter-insurgency waged by the U.S. government against all movement organizations:

A fundamental aspect of a people’s development is a conscious decision to declare their own view of reality, their aspirations, and their intentions… It should not be surprising that the Mexicano Indio descendents of the anglo-american conquest and colonization of Aztlan, who remain a subclass within the borders of white america, looked inward, embraced themselves as a legitimate people, and openly declared their own aspirations and intentions. Moreover, that this organic Chicano view of reality challenged the very economic foundation and philosophical assumptions of white america, should also be of no surprise… Thus along with the experience of other oppressed peoples held in captivity within corporate america, the Chicano Mexicano people symbolize the greatest historical contradiction to american imperialism in the southwest… At the height of the last period, 1965-75, certain historical dynamics forced the question of imperialism to slap white america squarely in the face in the international arena, i.e. Cuba 1959, Vietnam 1968, Chile 1970, Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde 1974, etc. The social upheaval of the 60’s and 70’s rapidly drove home the political similarities of the colonial oppressed peoples in the third world to the captive descendants of the conquered Mexicano Indios and enslaved Africans in the United States.

The significance of this last period must not be underestimated or overestimated. We must first recognize that this period [the Chicano Movement between 1965-1975] was a manifestation of 130 years of imperial domination, or what we now recognize as domestic neo-colonialism. More specifically, while this manifestation gave birth to modern Chicano Nationalism, the goal, de-colonization was never won. It is important to also note that most participants in the Chicano Movement did not, unfortunately, identify their struggle against oppression as a struggle against domestic (or internal) colonialism. This incomplete understanding of the objective conditions preempted the outcome of the last period… There are three general areas of discussion presented here which allow us to reflect on the most significant aspects of the last period: 1. the problem of ideology; 2. the role of organization; and 3. three, the role of the state.

- THE PROBLEM OF IDEOLOGY… A common misconception was that scientific analysis was for white radicals and armchair revolutionaries. This is not to place undue blame on the barrio, after all, barrio organizing was the most chingon thing you could do. Unfortunately, those Chicanos who were attempting to deal with ideology tended to uncritically accept the ideological direction of one or another north american leftist formation. This tendency was actually a natural development in relations between the colonial labor force and the white left…

- THE ROLE OF ORGANIZATION… Our major organizations lacked the organizational structure and experience that would allow for mass membership, material growth, the necessary guidelines and security checks for protection against infiltration by the colonial military and police forces… Within the ranks of the movement there existed a dislike for doing concrete organizational work, efficient administration, development of a communication network, report writing and documentation, record keeping, fundraising, resource development, etc., in other words the movement lacked a tradition of high level organization which included all the basic elements for a strong organization… Thus without an organized and mature formation to pull together, educate, and lead an effective struggle, all most Raza could do was to rebel in isolation, detached from other active liberation forces… Another major enemy that plagued the last period of struggle to the present, is the preponderance of liberal tendencies in the leading forces, both among individuals and organizations… This liberalism manifested itself in opportunism, individualism, hero and myth worship, laziness, male chauvinism, failure to work collectively, and personalism… when leadership differences developed within the movement, the absence of a strong organization with mechanisms to deal adequately with personal and political differences led to massive disruptions, divisions, and setbacks…

- THE ROLE OF THE STATE… Any analysis of the history of the Chicano Mexicano struggle for liberation must include… the covert and overt role of the colonial state… Key here is the basic understanding of the various forms of colonial military repression, e.g. frame ups, killings, beatings, intimidations, dis-information, and slander. Particularly effective was the counter intelligence program or COINTELPRO – with its ‘special’ investigation units in police departments in every major city in occupied America (United States)… The bourgeois print and electronic media contributed tremendously to the undermining of the Chicano Movement through its consistent falsification of information and the objectives of movement forces.

CONCLUSIONS ABOUT THE LAST PERIOD OF STRUGGLE

- The Chicano Mexicano people of Aztlan are among the indigenous people de las Americas, we are not Europeans.

- The economic condition of the Chicano Mexicano people is best summed up as a domestic colonialism.

- Domestic (or internal) neo-colonialism is the face of capitalist imperialism in the southwestern part of the United States.

- The last period of struggle was clearly the defeat of the Chicano Nationalist Movement (though not its total destruction).

- The absence of a cohesive ideology in the Chicano Movement also contributed to the failure of Chicano Mexicano liberation.

- An advanced, mature, disciplined, security conscious organization is the solution to Raza oppression.

- Openness, creativity, and morale are the fundamental elements for translating theory into practice, practice into critical analysis, and analysis into theory.

ONLY THE POWER THAT SPRINGS FROM THE DAY TO DAY POLITICAL STRUGGLE OF THE CHICANO MEXICANO NATIONALIST LIBERATION MOVEMENT CAN EVER LEAD TO A TRUE TRANSFORMATION OF SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC POWER IN AZTLAN.

We include this lengthy excerpt from 1986 as evidence of how we value debate within the movimiento as both correct and necessary, and to demonstrate how the issues that motivated much of the MEChA name change did not begin within MEChA. It is also clear that the critique we made of the movimento in 1986 was intended to be constructive. We identified our primary enemies within colonial-imperialist state power, but also critiqued backward tendencies within the movimiento. Most importantly, we consistently privileged raza working class communities over neo-colonial academic institutions and neoliberal individualism. We believe that the constructive characteristics of our 1986 critique of the Chicano Movement of the 1960s-70s are missing from the MEChA name change debate.

This analysis is the second of three parts of Unión del Barrio’s Report & Analysis On The 2019 MEChA National Conference. The third and final part will be published as soon as possible.

PART ONE: Our Report On The 2019 MEChA National Conference

PART TWO: We Disagree With The Decision To Change What M.E.Ch.A. Stands For

PART THREE: Social Media Woketivism Is A Representation Of Political Culture, Not The Real Thing